The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, stands as both a celebration of the game’s legends and a constant source of debate. Born from economic necessity during the Great Depression, the Hall has evolved from a local tourism initiative into a national shrine, though its history is steeped in mythmaking, shifting standards, and moral quandaries.

The Origins: A Town, a Myth, and a Business Plan

In the 1930s, Cooperstown was a struggling rural village. Stephen C. Clark, an heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune, saw tourism as the town’s salvation. He seized on the widely accepted, yet historically dubious, claim that baseball originated in Cooperstown in 1839 with Abner Doubleday. Clark understood that narrative mattered more than accuracy, and leveraged this myth to attract national attention.

Clark secured endorsements from Major League Baseball, which recognized a centralized hall of fame could elevate the sport’s cultural standing after scandals like the Black Sox affair. In 1936, the first election was held, with Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson, and Walter Johnson becoming the inaugural inductees. The process was flawed from the start; no one was unanimous, and even banned players were eligible for consideration.

Evolving Standards and Controversial Choices

Over the decades, the Hall’s standards fluctuated. The early selections were clear-cut legends. But as the pool of candidates grew, the criteria blurred. The rise of sabermetrics in the late 20th century introduced advanced statistical analysis (like WAR and OPS+) into the debate, creating friction between traditionalists and data-driven voters.

One of the Hall’s most glaring omissions was the long neglect of Negro League players. Though formally recognized as major leagues in 1971, their inclusion lagged for decades. Satchel Paige’s induction in 1971 was a landmark, but the process was slow, relying on incomplete records and eyewitness accounts.

The Steroid Era and Pete Rose: Unresolved Conflicts

The late 1990s and early 2000s brought the most enduring controversies: performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) and Pete Rose’s lifetime ban for betting on games. Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, despite statistically dominant careers, fell short of induction amid accusations of steroid use. The Hall’s refusal to seat Rose, baseball’s all-time hits leader, continues to ignite debate.

These cases reveal a fundamental tension: Should the Hall honor players who violated the rules, even if their statistical achievements are undeniable? The debate highlights the Hall’s struggle to reconcile its role as a historical archive with its responsibility to uphold ethical standards.

The Modern Process and Lasting Legacy

Today, the Hall’s induction process involves both the Baseball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA) and various era committees. Players remain on the ballot for ten years, needing 75% of the vote to enter. The process is far from perfect, but it reflects an ongoing effort to balance tradition, statistics, and moral considerations.

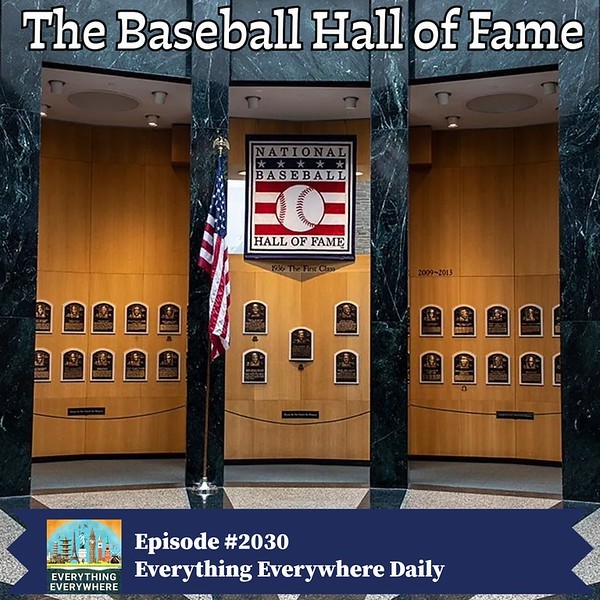

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum is more than a collection of plaques; it’s a mirror reflecting baseball’s complex history. From its humble origins as a local economic project to its status as the sport’s ultimate honor, the Hall continues to provoke debate, celebrate greatness, and preserve the enduring legacy of America’s pastime.