The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943 stands as a harrowing yet profoundly significant event in World War II, embodying the desperate resistance of Jewish people against Nazi Germany’s genocidal policies. For nearly a month, the residents of the Warsaw Ghetto, facing certain death in concentration camps, fought back against overwhelming military force. This uprising, the largest Jewish revolt during the war, became a potent symbol of defiance in the face of systematic annihilation.

A Nation Fragmented: Poland Before the War

Before the Nazi invasion, Poland was a newly independent nation, forged in 1918 from territories previously controlled by Russia, Germany, and Austria-Hungary – a result of the Treaty of Versailles. The Second Polish Republic was remarkably diverse, with roughly one-third of its 35 million inhabitants identifying as Jewish, German, Ukrainian, Belarusian, or Lithuanian. This diversity, however, fostered deep ethnic tensions. Germans were viewed with suspicion, Ukrainians resented forced assimilation (“polonization”), and Jews faced widespread antisemitism. Poland’s weak industrial base and precarious position between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany further destabilized the country, making it a prime target for both aggressive powers.

Invasion and Occupation: The Creation of Ghettos

These fears materialized on September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland, followed by the Soviet Union on September 17. Within 35 days, Poland was partitioned, with Germany seizing the west, including Warsaw, and the Soviets occupying the east until 1941. The Nazi occupation immediately brought brutal anti-Semitic policies: Jews were forced to wear identifying armbands, their schools were closed, and their property was confiscated.

Under Reinhard Heydrich, a key architect of the “Final Solution,” the Nazis ordered the forced relocation of Jews into segregated ghettos. These ghettos were not simply residential areas but deliberately constructed sites of deprivation, designed to showcase the Nazis’ twisted propaganda that Jews were inherently “dirty” and disease-ridden. The first ghetto opened in Piotrków in October 1939, followed by hundreds more across Poland.

The Warsaw Ghetto: A Prison of Suffering

Established in October 1940, the Warsaw Ghetto became the largest Jewish ghetto in Europe, crammed with 400,000 people within just 1.3 square miles. Conditions were horrific: an average of 7.2 people lived per room, food rations were starvation-level (just 1,125 calories per day), and disease ran rampant. Between 1940 and mid-1942, an estimated 83,000 people died from starvation, disease, and exposure. Smugglers risked their lives to bring in food and medicine, but even these efforts only partially alleviated the suffering.

The Deportations and the Spark of Resistance

In July 1942, the Nazis began mass deportations from Warsaw to the Treblinka extermination camp. Eyewitness accounts confirmed the rumors of systematic killings, but the Jewish Council initially denied them. Despite this denial, resistance groups began warning people that deportation meant certain death. When the head of the Jewish Council, Adam Czerniaków, was pressured to compile a list of deportees, he took his own life rather than cooperate.

The deportations continued brutally, sending over half of the ghetto’s population to Treblinka by September 1942. This desperation spurred the formation of armed resistance groups: the Jewish Fighting Organization (?OB), composed of younger militants, and the Jewish Military Union (ZZW), representing right-wing Jewish factions. Both groups sought arms and support from the Polish Underground Resistance, including Jan Karski, a courier for the exiled Polish government.

The Uprising: A Final Act of Defiance

By early 1943, tensions reached a breaking point. The Nazis planned to liquidate the entire Warsaw Ghetto on April 19, 1943 – strategically timed to coincide with the eve of Passover and Hitler’s birthday. The resistance fighters were prepared, though vastly outnumbered: only about 1,000 armed combatants against the full force of the SS and German military.

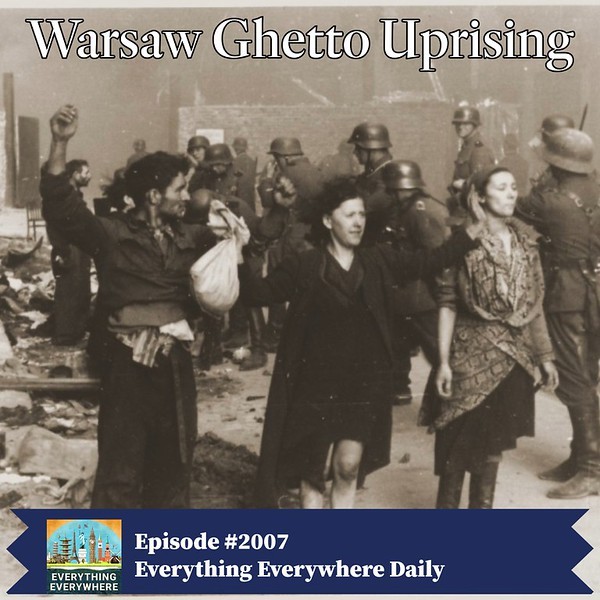

When the Nazis entered the ghetto, they were met with fierce resistance. Molotov cocktails, grenades, and improvised mines were used to ambush German troops. The fighting lasted for weeks, with the resistance fighters using their knowledge of the ghetto’s labyrinthine streets to inflict casualties. The Nazis responded with brutal tactics: setting buildings ablaze, gassing bunkers, and flooding sewers to deny escape routes.

On May 8, the ?OB headquarters was surrounded, and the remaining leaders were forced into a bunker where they either died of asphyxiation or committed suicide rather than surrender. The uprising officially ended on May 16, 1943. The Nazis celebrated their victory by demolishing the Great Synagogue of Warsaw, one of the few buildings left standing.

The Aftermath: A Legacy of Courage

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising resulted in the deaths of roughly 13,000 Jews, with another 42,000 deported to concentration camps. While German casualty figures were disputed (officially claimed at 110, including 17 killed), the uprising demonstrated that even in the face of certain death, victims of genocide would not go quietly.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the first large-scale armed resistance by Jews against Nazi Germany, shattering the myth of Jewish passivity and leaving behind a lasting legacy of courage and defiance in the darkest chapter of human history. It remains a powerful reminder that even in the most hopeless situations, the human spirit can refuse to be broken.