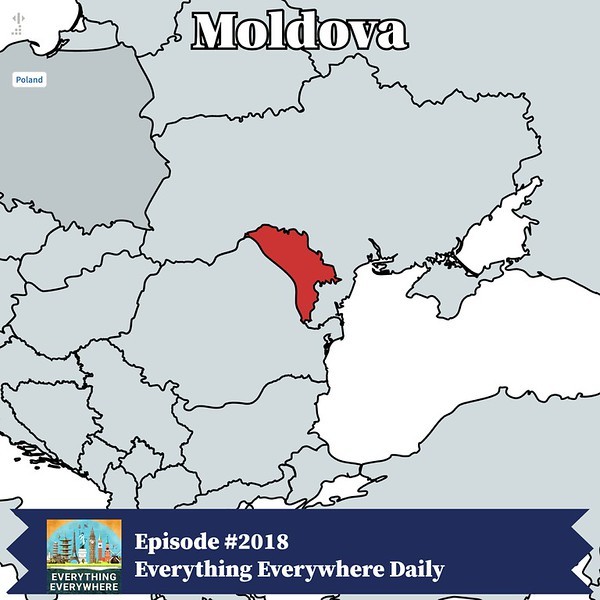

Moldova, a landlocked nation nestled between Romania and Ukraine, boasts a remarkably complex history shaped by its strategic location as both a cultural crossroads and a buffer between empires. For millennia, armies and peoples have traversed its territory, leaving behind layers of influence that define the country today. This episode unpacks Moldova’s journey from ancient settlements to modern independence, exploring the forces that have shaped its identity and the challenges it faces as it navigates the 21st century.

Ancient Roots and Medieval Emergence

The region now known as Moldova has been inhabited since prehistoric times, with evidence of settlements dating back to the Paleolithic era. Between 5500 and 2750 BC, the Cucuteni-Trypillia civilization flourished, leaving behind sophisticated pottery and settlements that demonstrate early agricultural advancements. Later, the Dacians, a Thracian people, established a powerful kingdom until the Roman conquest under Emperor Trajan in 106 AD. Though Roman control was limited, their linguistic and cultural legacy endures in the Romanian language still spoken by Moldovans today.

The centuries following Roman withdrawal saw waves of migrations – Goths, Huns, Avars, Bulgars, Magyars, and Slavs – creating an extremely diverse ethnic landscape. By the early medieval period, Slavic influence grew, impacting language and culture. The medieval Principality of Moldavia emerged around 1359 under Dragoș, but truly solidified under Bogdan I in 1365, stretching from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dniester River. This young principality immediately faced pressure from the Kingdom of Hungary and the rising Ottoman Empire.

The Golden Age and Ottoman Vassalage

Stephen the Great, ruling from 1457 to 1504, ushered in a golden age for Moldavia. A skilled military commander and diplomat, he defended the principality against Ottoman, Hungarian, and Polish incursions, fortifying it with monasteries and fortresses that stand today. Despite his successes, Moldavia could not indefinitely resist Ottoman pressure; by 1538, under Petru Rareș, it became an Ottoman vassal state. Unlike territories fully absorbed, Moldavia retained autonomy, including its own prince and administration, as the Ottomans prioritized tribute over direct rule.

The following centuries saw Moldova function as a buffer zone between competing empires. The principality maintained nominal independence but faced increasing Ottoman interference and corruption, culminating in the appointment of Greek rulers from Constantinople in 1711. Russia’s growing power added further complexity, with Russo-Turkish Wars repeatedly devastating Moldavian territory. The Treaty of Bucharest in 1812 proved transformative, ceding the eastern half of Moldavia – Bessarabia – to the Russian Empire. This division split the historical principality, creating a boundary with lasting consequences.

Russian Rule and National Awakening

Under Russian rule, Bessarabia underwent significant transformation. Colonization by Ukrainians, Russians, Germans, Bulgarians, and Gagauz Turks increased ethnic diversity, while the Russian Empire attempted to diminish Romanian cultural identity through suppression of the Romanian language. Despite these policies, a national awakening among Romanian-speaking intellectuals emerged in the 19th century, though weaker than elsewhere due to Russian repression.

The collapse of the Russian Empire during World War I created an opportunity for change. In 1917, a Moldovan assembly declared autonomy, followed by independence in 1918, culminating in unification with Romania in April of that year. This move was celebrated by ethnic Romanians but contested by Soviet Russia, which never recognized the annexation. Interwar Bessarabia saw modernization efforts, but economic underdevelopment persisted, and ethnic minorities felt marginalized.

Soviet Occupation and Post-Soviet Independence

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 assigned Bessarabia to the Soviet sphere of influence. In June 1940, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum, and Romania evacuated the province without resistance. The Soviets established the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, deporting “class enemies” and intellectuals to Siberia and Central Asia. When Romania allied with Nazi Germany in 1941, Bessarabia briefly returned to Romanian control, but brutal policies were enacted against Jews and Roma.

Soviet reconquest in 1944 brought further deportations and a devastating famine exacerbated by Soviet agricultural policies. The goal was clear: break resistance and suppress Romanian identity. The Soviet government systematically promoted a distinct Moldovan identity, imposing the Cyrillic alphabet despite the language being identical to Romanian. Russian became dominant in urban areas, ensuring Communist Party and administrative advancement.

Under Gorbachev’s reforms in the 1980s, suppressed national feelings reemerged. The Moldovan Popular Front advocated for greater autonomy and linguistic rights, leading to the adoption of laws reinstating Moldovan (Romanian) as the state language and the Latin alphabet in 1989. This alarmed Russian-speaking minorities, sparking separatist movements in Transnistria.

Moldova declared independence on August 27, 1991, as the Soviet Union collapsed. The newly independent state faced immediate challenges, including the unresolved conflict with Transnistria, where Russian-backed separatists resisted government control. A ceasefire in 1992 left Transnistria as a de facto independent state, unrecognized internationally but effectively outside Moldovan control.

The Future of Moldova

Today, Moldova is not a member of the EU or NATO, but the prospect of unification with Romania remains a recurring debate. Supporters argue for a fast-track path to European integration, while opponents cite internal divisions and Russian interference. President Maia Sandu has stated she would vote for unification if put to a referendum. The wine industry remains culturally and economically important, but Moldova’s history reveals a small nation perpetually caught between larger powers, struggling to maintain its identity. Its future will depend on navigating this balancing act between East and West while resolving the Transnistrian conflict.